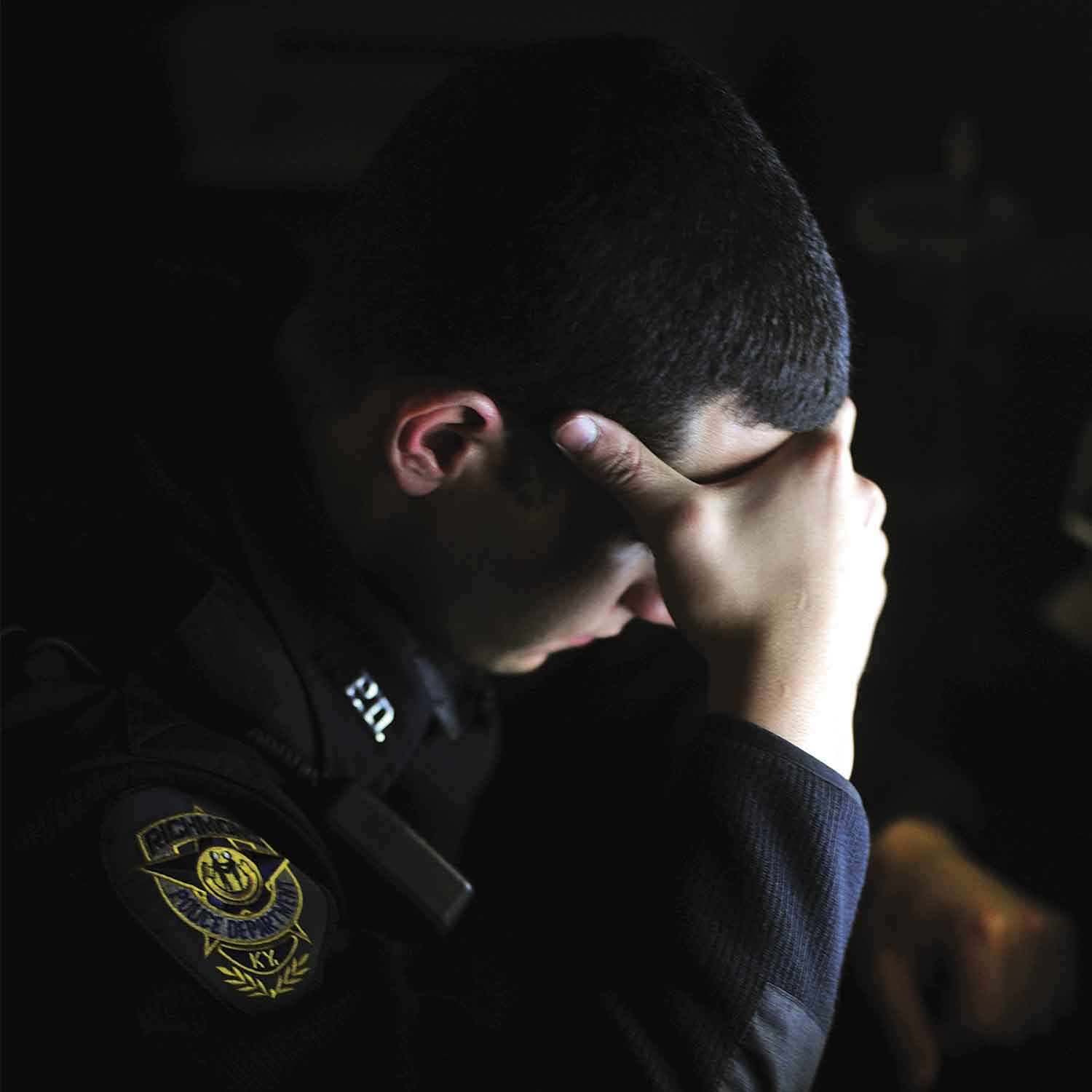

The scars you can't see are the hardest to heal.

"The scars you can't see are the hardest to heal."

– Astrid Alauda

What happens when the call is over, but the mind won’t letgo? First responders; firefighters,police officers, and emergency medicalpersonnel—spend their careers witnessing humanity at its most vulnerable. Theypull people from burning buildings, administer CPR to the unconscious, andstand face-to-face with life’s most harrowing moments. But beyond the flashinglights and emergency calls, there’s a hidden reality few acknowledge: theweight of what they carry long after the crisis ends.

While their uniforms show no visible scars, their minds bearwounds that linger in silence. The emotional burden of witnessing loss,suffering, and tragedy accumulates over time, leaving a lasting imprint. Yet,unlike physical injuries, these invisible wounds often go unnoticed, untreated,and unspoken.

How does one recover from what they can’t forget?

A mental state where individuals worry that they might havedone something to save the victim of a tragedy. A paramedic who loses a patientduring transport to the hospital, a police officer who cannot prevent a violentact, or a firefighter who could not rescue everyone in a burning building—Eachof these experiences leaves a lasting psychological imprint, echoing in theirminds long after the sirens fall silent.

As reported in a study published in the Journal ofOccupational Health Psychology, 64% of first responders experience chronicguilt and re-play traumatic calls over and over in their heads (Stanley et al.,2016). This cycle of self-blame wears away mental health and raises the stakesfor burnout and PTSD.

The fight-or-flight mechanism that makes responders alert incrisis situations doesn't just flip off when they leave work. Many firstresponders experience persistent hypervigilance, leaving their bodies in aconstant state of alertness, leading to chronic stress, sleep disturbances, andan inability to relax.

Studies suggest that chronic stress from hypervigilance canelevate cortisol levels, increasing the risk of cardiovascular diseases(Maslach & Leiter, 2016).

Police officers have reported having trouble enteringcrowded areas without scanning for threats, and EMTs talk about alwayslistening for ghost sirens. This constant mental fatigue makes it hard forresponders to be fully engaged in personal relationships and lead normal lives.

First responders not only experience direct trauma but alsotake in the pain of their clients—a condition referred to as vicarious trauma.Repeated exposure to suffering rewires the brain’s emotional processing,leading to compassion fatigue and emotional detachment.

Dr. Charles Figley, a trauma psychology expert, writes thatfirst responders tend to suffer from secondary PTSD, wherein the pain they seein others hurts them as much as if they had been hurt themselves (The Cost ofCaring, 2013).

Trauma doesn't remain at work; it accompanies respondershome. Many first responders emotionally shut down as a defense mechanism,creating distance between themselves and their loved ones.This builds distanceover time between them and their loved ones.

The National Institute of Justice study revealed thatdivorce rates for firefighters and police officers are greater than the ratesof the overall population, both stemming primarily from emotional withdrawal aswell as failure to deal with trauma in a constructive manner (Fox et al.,2015). These members of a firefighter's family are frequently cited to feelalienated, knowing that they don't comprehend the actions of loved ones.

In order to deal with stress, some responders use alcohol,prescription drugs, or dangerous behaviors. The National Institute on DrugAbuse (2020) states that 20% of firefighters and police officers have substanceuse disorders—nearly double the national rate.Most fear asking for assistancebecause of the stigma of mental illness in emergency careers, which often stemsfrom cultural expectations to appear strong and resilient, as well as fear ofjob repercussions or being perceived as unfit for duty.

Unaddressed trauma also raises the suicide risk. RudermanFamily Foundation (2018) discovered that more first responders die by suicideannually than they do in the line of duty. This finding highlights theimmediate need for enhanced mental health support and crisis intervention.

“Sometimes, the most healing words are, ‘I understandbecause I’ve been there too.”

Peer support programs, such as those provided by MyOmnia’sInformed-Wholeness Model, create safe spaces for responders to share theirburdens. Studies show that peer-led mental health groups reduce PTSD symptomsand increase resilience (Previdence, 2024).

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Eye MovementDesensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), and Trauma-Focused Therapy areevidence-based ways to assist responders to process trauma in a positive manner(Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). CBT helps reframe distressing thoughts, whileEMDR uses guided eye movements to process trauma. Therapy is not weakness; itis a step towards regaining mental clarity.

Psychologists suggest that symbolic acts, like writingletters to lost patients, create a sense of closure, allowing responders toprocess grief constructively (Koenig, 2012). These activities assist respondersin overcoming without the impression that they are leaving behind memories ofthose whom they could not save.

First responders dedicate their lives to saving others, butwho is saving them? The burden they carry is invisible, but its weight isundeniable. Healing begins with awareness, conversation, and support. Breakingthe silence is not weakness—it is courage. Seeking help is not surrender—it isstrength.

Trauma’s echoes need not dictate a responder’s future, theycan instead become the foundation for healing and growth. If you or someone youknow is struggling, reach out. No one should carry this weight alone. You arenot alone.

“Sometimes, we must be our own heroes because no one else iscoming to save us.”

– Rupi Kaur